I was sixteen when I told my mom I wanted a sex change.

She took a beat of silence, and said: “You can do whatever you want once you’re eighteen.”

Of course I understood that, while she had not said “no,” there was some reticence in that response. For what would change upon my turning eighteen? Only her legal power to stop me making such a move.

I puzzled over her (very gentle) dissuasion. My mom was the person who made me watch The Rocky Horror Picture Show when I was 12. I wasn’t interested, myself; Janet Weiss smacked of Sandra Dee, and Brad Majors was not my type, so I tried to walk away from it several times in the first quarter of an hour. I much preferred my film version of Cats, with John Partridge as Rum Tum Tugger in all his gyrating, Spandexed glory. But Mom insisted I stay until Tim Curry came down that elevator shaft.

“Is that a man or a woman?” I asked.

She nodded toward the TV. “Just watch.”

But what I did, when I whipped my head back toward that screen, was not so passive as just watching. I was cataloging Dr. Frank N. Furter’s every article and eyebrow twitch for science. I had never known something like this was possible. And if this was real–if enough people existed to produce a film, a scene, a character such as this–what else was there to find? I wanted to pin it all down, for keeping in the curio cabinet in my head. And while I was transfixed, Tim Curry’s velvet voice reached down my own throat, like Ursula’s spell—but instead of a vocal cord, it was a heartstring he took hold of.

Mom knew that he had me. The moment he had gone away, back up the elevator, I turned and asked again: “Was that a man or a woman?”

This time, eyes twinkling, she replied: “Does it matter?”

Mom joked in the years after that her options at the time were, either, to show me Rocky Horror or to have “the sex talk” with me herself. And certainly her decision colored my sexual awakening. I spent every October of my adolescence at Rocky. One year, fresh out of spending money, the director of the live show stopped me leaving after the 8pm performance, and comped my tickets for the midnight one, because he needed me: I knew every call-back. Another year, on closing night, when every member of the cast was given a rose, I got one, too. I made myself a fixture, and meanwhile I fell hard (at a distance) for every Frank N. Furter I encountered—and one towering, teenaged Riff Raff.

I was in acting classes myself then, working on scenes for recitals that tied together the work of the ballet and tap cohorts as well. Rocky Horror was a language I could use to get closer to the kind of boys I was drawn to, all my different Frank N. Furter t-shirts acting as beacons. I have distinct memories of the star ballet boy—a redhead of lithe limb and princely presence—who generally had time for no one, but who would on purpose find me (me!) in the backstage corridor of our practice space, and whisper a line of “The Time Warp” close enough to blush my ear with his breath. I had no hope of answering; he always at the other end of the hall by the time I could turn my head. But he looked back, to see his effect on my face, before he disappeared.

None of these experiences materialized into anything like a relationship. Either my feelings went unexpressed entirely, or else I did express them to learn explicitly that they were not returned. But you mustn’t imagine, dear reader, that I was ignorant about the kind of boy I was drawn to. I knew that they were very probably interested in other boys. But here’s the thing: the revelation of Tim Curry’s Frank N. Furter, for me, was not just “whoa, I like dudes who like dudes.” It was also: “oh, dudes who like Brad can also like Janet.” Once that suggestion was made, outside of myself, I felt around inside myself and affirmed it there, too: I have never, up to now, admitted widely that I was pursuing girls my age, as well as boys, as a teen. In fact, my first real adolescent relationship was with a girl, and lasted several months. I was capable of wanting either.

And if I could do it, so could anyone.

Thus, my confidence—not ignorance—in presenting myself before all of them (Riff Raff, ballet boy, and others) with much vulnerability and some hope: as far as I was concerned, my fate was not predetermined by my gender, but rested on each individual’s pronouncement on me. Just because one gender-subversive person said no did not mean that all future such people would say the same.

Not that I bore all the rejection easily.

On an eighth-grade field trip to NYC to see Phantom of the Opera, I pressed my face against the window, headphones on, mind in the middle of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, probably, or else Modest Mouse spreading the Good News for People Who Love Bad News. I shut myself away all the time, staring out as the world went by, acutely feeling my loneliness. But on this day, a vividly blue eye peeked back, through the gap between the coach bus seat and that window, at me.

It blinked. A shift. Lips. A pretty boy I knew by sight—someone I’d seen when I went to visit my favorite English teacher. He wanted to say something to me.

I pushed my headphones down around my neck.

“Tragic,” he whispered, “that so beautiful a girl should look so sad.”

And that girl smiled henceforth, through what was then a date. The first of many.

How refreshing, to be pursued—and by my sort of boy, too. Unfortunately, that boy would use Rocky Horror against me. When I said I wasn’t ready for a certain sex act, he said, “’Don’t dream it, be it,’ right?”

I had had to say “no” a second time, so I resolved never to call him again.

When he transferred to my high school two years later, he was out as gay. Actually, I don’t know how widely it was known. But he told me. He also flirted with me in study hall, asking me details about my romantic life (which I was too proud of not to share), and disparaging the boyfriend I was then dating. In ways subtle and overt, he suggested himself as a better alternative for me.

I had not forgiven the attempt at coercion from when we were younger, and held the line. But I registered his desire for me, and noted it down. Gay, I understood, was an only mostly useful short-hand for him: he was generally attracted to boys. He was also still attracted specifically to me. And I was a girl.

Wasn’t I?

I had been watching Hedwig and the Angry Inch a lot, the year I said I wanted a sex change. I did that—watched and rewatched movies, played and replayed albums, until I could recite them word-perfect, play them back in my head. Maybe Mom said what she said, about doing what I wanted when I was eighteen, as a way to make sure it wasn’t just a flavor of the week kind of thing. Monkey see, monkey do.

Except, for most people the take-away from Hedwig would probably be “monkey, don’t,”—as things don’t go so great for our titular heroine. John Cameron Mitchell makes no secret of how rough this particular road to self-actualization is, in the world such as it is.

And, by the way, my rewatch obsession right before Hedwig had been the newest Jesus Christ Superstar. I fell head over heels for Glenn Carter, but the film did not change my agnosticism.

The truth is, Hedwig was a push down a path I had already been walking. My high school encouraged us to come to school in costume on Halloween. The first year I went as Eric Draven from The Crow. The next year I went as Jack Sparrow. The next year I went as Eric Draven again, Mom was a little surprised. Hadn’t I already done that one? Why do it again?

I shrugged and said I liked him. I felt I could not, should not, say the fuller thing. That I liked it: the experience. That is, I liked that, by following the roadmap of these characters’ distinctive face make-up, and by donning certain identifying costume pieces—electrical tape around my hands for Eric, a tricorn for Jack—people might read me as a boy.

I was more conscious of myself, those days. I sat up straighter. I held people’s gaze instead of avoiding eye contact. I usually only raised my hand in English class, but on Halloween I tried my hand at everything—my electrical-taped hand, up high, so people would look at it, look at me, look, and maybe see, for just one second, a boy instead of a girl.

After I told my mother about what I wanted, I started going to school in jeans and t-shirts with my hair slicked back off my forehead, and asked the emo-band boys in my Civics class to call me Brian. And, for a wonder, they did it. Nobody made a big deal out of it. They made a point of trying to include me more in their conversations, when they might easily have distanced themselves.

Discomfort came more quietly, from within, before my bedroom mirror. Without the help of a costume, of a specific character to be other than myself, I could not believe in me-as-a-boy. I was too short, my face was too round, my breasts too big—which was especially infuriating, because as a girl I was very aware that they were considered too small.

But dammit, I liked them. I thought they were just right. For me.

Not measuring up to a standard was an ache I knew well, as someone with cerebral palsy. I already couldn’t walk the same as my peers. I already couldn’t do most of the things they could do: even something so normal as walking down a few steps without a railing is impossible for me.

Looking in my mirror, I found I just did not want to set myself another challenge. The very thought exhausted me. I fled back to the gender presentation of least resistance.

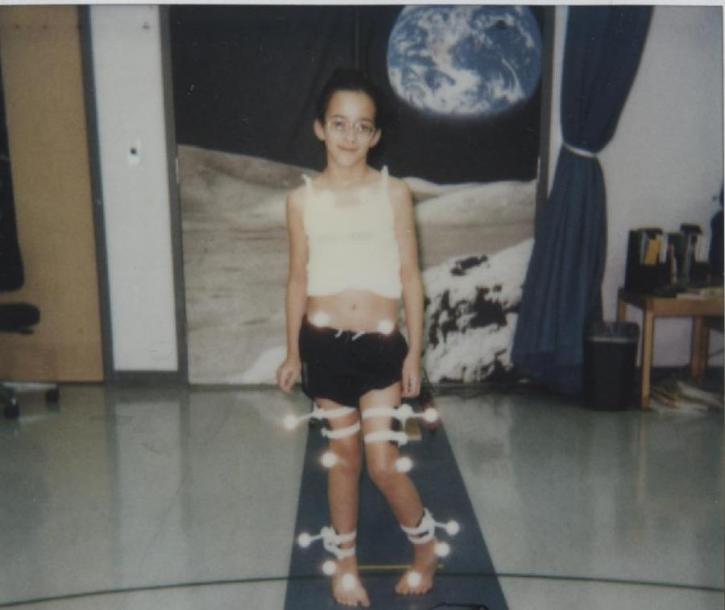

That, I think, is the real reason my mom said to wait: not to pass a judgment, but to make me take a breath, first. What I was talking about was another surgery or two, and in my young life I had already been through four big ones. I had had to relearn how to walk when I was ten. I got six new surgical scars on my legs before I got breasts. I had to turn my attention so completely to the progress of my gait that I was surprised, one day, to look up and find myself with hips. My relationship with my body was new, still, in so many ways.

Did I want to be more different? Did I want another reason to look at myself and think close, but not quite?

In practice, no. I couldn’t take that on. I had to acknowledge how much of my energies went to carrying myself, to accepting myself, in the body I had, as it was. Sometimes, making a change is a self-loving step. For me, in this case, the more self-loving thing was to stay the same.

But I wasn’t about to deny my gender-bendy insides. I bought a binder for when I was feeling fellowy. I started telling people “I aspire toward androgyny.” I made myself a student of gender in college, and delighted to learn in sociology classes all about what a deliberate performance gender is—and how different the expectations of the performances are, from culture to culture. I made myself comfortable again in the idea that my biological sex need not limit me at all: not my behavior, my aesthetic, my aspirations, or my possible lovers.

Yet I thought of myself as a heterosexual woman—even as I salivated for months over one of my Student Center lady friends, who was regrettably dating a rather gross guy. I was also dating a guy, at the time. Sometimes I wonder if we were eyeing each other, she and I, and never knew.

Whenever I considered identifying as bisexual, the knee-jerk thought would come: I am not attracted to most women, only some. And I say this part in case anyone else needs the kick in the brain that I needed. Are you ready for it?

I’m not attracted to most men, either.

This is the thing that lots of “nice guys” don’t get, right? That just because you’re a woman who likes men doesn’t mean you automatically like every man. I realized: the sub-set of men I am attracted to is a minority of men. And I don’t think my queer taste has anything to do with that. Another (het) woman’s taste in men might be different, but she certainly has a taste, period. I suggest that, no matter what her taste is, there are certainly plenty of men it necessarily precludes from her desire.

It would be an illuminating exercise for anyone, I think, to sit in a mall or park and try what I tried: noticing every example of my professed sexual preference that I was, nevertheless, not attracted to. My liking a man, it turns out, is the same sort of unusual occurrence as my liking a woman—I thought of the latter as the only surprise, of the two, because I have been taught to expect to like men.

Lots of folks know that I spent a decade of my adult life in a closed throuple with two queer men. I’ll tell you this: I might be in it, still, were people’s expectations about gender and sexuality not so rigid—even within the queer community, even among our supportive friends and family, even within my partners and myself. I wish I had believed harder, had fought to defend that truth which has been suggested over and over to me by my lived experience:

Every instance of desire is, in fact, exceptional.

At least, I am the healthier now for treating each of them as such. Searching less for vindication in someone’s gender performance, or their sexual history, and focusing instead on the solid substance of the specific connection between that person and me.

“Do you want me?” is not a question that can be answered by educated guess—based on probabilities, then marked on a sliding scale.

“Do you want me?” is a binary question—the only binary I really give a shit about.

TL;DR: I’m a genderqueer, pansexual person (and I don’t care what pronouns you use for me in good faith). Sorry I’m just telling you now—it happened while I wasn’t looking.